Third Spoonful

Inside Green Gulch Farm’s monastery kitchen, where they remember how you eat

WRITER Melody Saradpon

PHOTOGRAPHER Tri Nguyen

Zenko Montgomery, Tenzo of Green Gulch’s kitchen

The man who made me cry is named after a tiger. Zenko Montgomery, the Tenzo (head cook) at Green Gulch Farm—his name translates to a zen tiger taking to the mountains—gestures towards four large steel appliances, humming in the monastery kitchen. He introduces the convection oven as Ekufū (“Nourishing Wind”) and the heavyset six-burner range as Seien (“Sacred Flame”) with the tender attention most people reserve for sleeping children. He smiles, nodding in reverence to the remaining two. I learn the griddle is named Tetsuryū (“Iron Dragon”); the four-burner range, Kōki (“Dazzling Works”).

Zenko lives here, in this valley 30 minutes from San Francisco near Muir Beach, where the Zen center has been making people cry for 50 years.

I’m here because I was one of them. Four weeks ago: tortilla soup, third spoonful, sudden tears in the dining hall. Gentle, but insistent, the kind that made me grateful for the ritual silence and corner window seat. Now, I’m back, trying to understand what kind of cooking can do that to a person.

Turns out, I’m not special.

When I tell Zenko about the soup incident, he laughs with the hearty ease of someone who’s seen this before. Then he grins—warm, knowing, the kind that suggests he’s about to share something slightly absurd but absolutely true.

“The dish that’s made people cry the most,” he tells me, “is rolled oats, applesauce, cheese cubes, and toasted almonds. It’s like apple pie with cheese, basically deconstructed.”

The simplicity throws me. Cafeteria food, essentially. “How long have you been serving this?”

“It’s a recipe from the early ‘70s when [San Francisco] Zen Center was founded,” he says. “We’ve just been cooking it for 50 years.”

I try to picture it: 50 years of people—longtime practitioners, weekend guests, retreat participants—moved to tears by oatmeal and cheese cubes. When I ask why he thinks it affects people this way, he considers the question.

“I feel like this practice brings you closer to yourself, right?” he says. “And gets you out of the world of performing or wearing a mask for anyone else.” He pauses, quiet and thoughtful, suggesting something philosophical is coming. Taking advantage, I lean in with a big question.

“How would you describe zen comfort food?” I watch his response.

“Oh, gosh. We cook just real-ass comfort food too,” he laughs. The levity enters like sunshine.

Umpan mealtime gong outside the dining hall

He tells me about serving mac and cheese after groups of people sat in silent meditation from 5am to 7:30pm for an all-day monastic practice. But Zenko draws menu inspiration from everywhere: one night, Jamaican; the next, Korean; then Georgian or Hawaiian soul food.

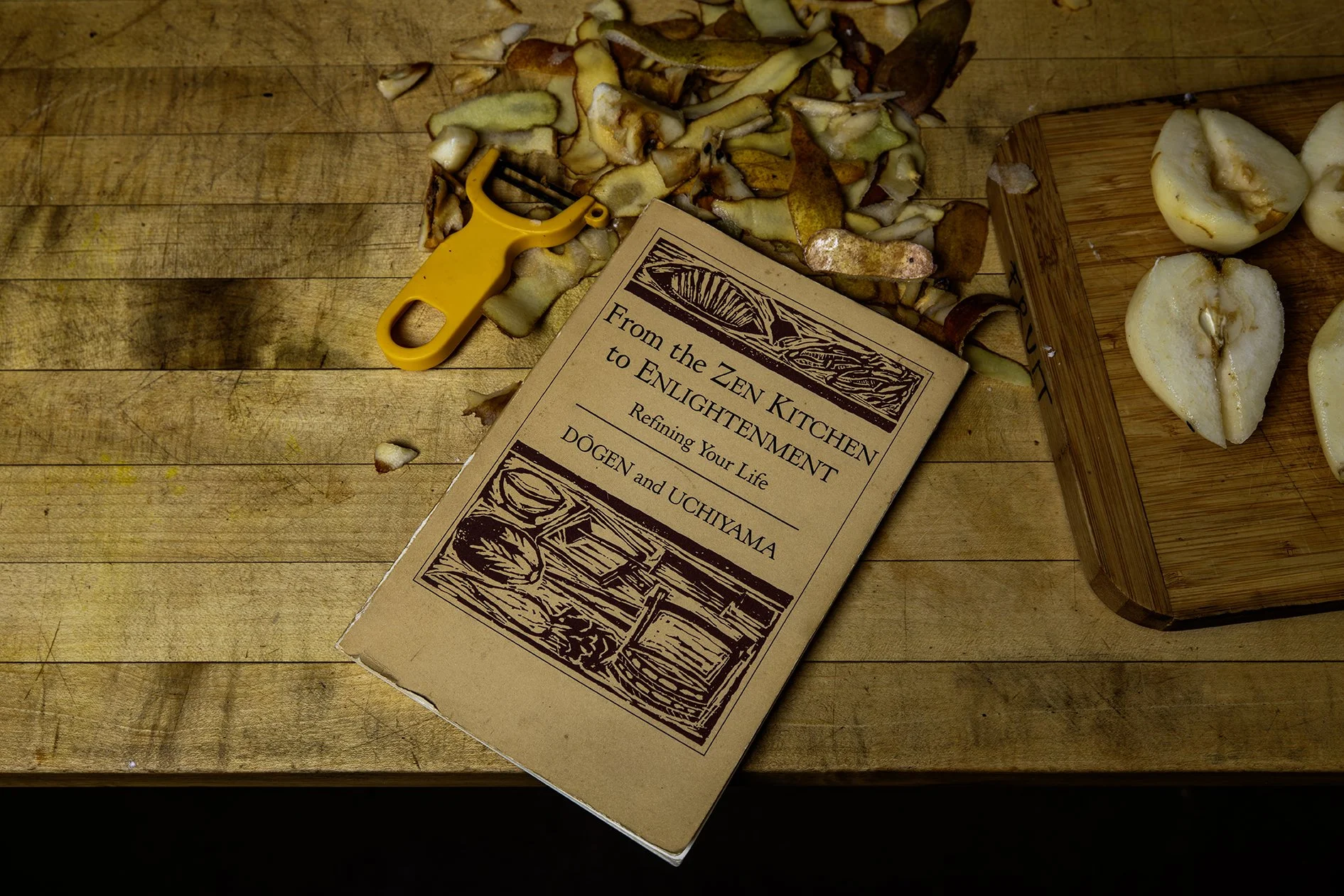

His cooking philosophy is rooted in the Tenzo Kyokun, a 13-century text for the monastery cook written by Dogen, founder of the Soto Zen school. “We chant it every day in the kitchen,” he tells me. “It’s all about kitchen mindfulness.”

“The Buddha way is actualized by rolling up your sleeves,” Zenko quotes, his favorite aphorism. This guides the entire community, from kitchen to fields.

Each night, the Tenzo Kyokun instructs cooks to close their eyes and consider each and every one of their 80-plus members—the same community that sits in silence each morning, that tends the farm with the same deliberate care. “To judge how much they’re gonna eat or if they’re a little sick and eat a little less,” Zenko explains. He calls it “farmer zen”—not the elite samurai practice but the common wisdom of country temples. He knows who needs softer food, who’s recovering, who might be extra hungry from farm work. This attention saturates everything at Green Gulch.

A resident apprentice in the orchard

Every object receives consideration—brooms are positioned to preserve their bristles, ovens are given a full week off at New Year’s. When I ask Zenko to define comfort without using warm, he says simply: “Intimacy is comfort. When you’re distant from what you’re doing or distant from yourself, that’s uncomfortable. To be intimate with ingredients, intimate with your body. And intimate with the present.”

To demonstrate, he shows he his famous three-bean miso soup. “It can take whatever you put into it. If all you have is one shriveled carrot and half an onion and a little bit of sesame oil, you can make this soup.”

“You’re forgiven for whatever you add.” The way he says it, I understand this extends beyond the kitchen.

Zenko’s Foggy Monk Soup on a saddle